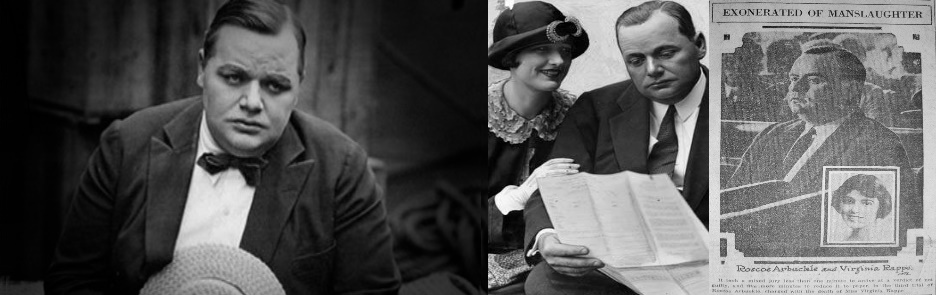

...Exonerated three times. Roscoe Arbuckle was found to be completely innocent of the crime(s) he had been accused of, falsified incrimination covering up the blackmail and lies perpetrated against him by a series of people.

SEPTEMBER 13, 2021 / THE AUTHORS

NOTE: The following article is taken from www.peoplevsarbuckle.com

________________________________"[The following is taken from or work-in-progress, in which we describe the testimony at the second session of the Coroner’s Court, conducted by San Francisco County Coroner T. B. W. Leland before an all-male jury. Following her appearance, her importance to the prosecution of Arbuckle quickly faded. Nevertheless, District Attorney Matthew Brady kept open the possibility that she might appear in court again as late as March 1922, during the third Arbuckle trial.

We have various theories about why Delmont wasn’t put on the stand again at any subsequent venue related to the Arbuckle case. One of these is that much of what she stated behind closed doors and even in the Coroner’s Court was “unprintable.” It is usually assumed that her account of events differed so greatly from others’ statements that it was deemed unreliable and too much of a risk to the prosecution.

When the defense had an opportunity to call her to the stand, they refused. Of course, her describing the real nature of Arbuckle’s party may have been the cause. By having his Labor Day party in a hotel suite, Arbuckle may have thought he’d found a loophole in a Hollywood maxim cited in Evelyn Waugh’s The Loved One, to wit, “never do before the camera what you would not do at home and never do at home what you would not do before the camera.”]

Still dressed in black, Maude Delmont was again aided by a policewoman who, beside her, made Delmont appear taller. Delmont looked tense, fragile, ten years older than her real age (late thirties), and hardly what one would imagine of a flinty, hard-drinking daughter of a frontier dentist. The corners of her mouth drooped, her dark hair showed strands of gray. Kinder reporters saw her crow’s feet as “lines of sorrow” that suggested an “intimacy of years” spent with Rappe. The intimacy was quickly revealed to be less than a week. “But friendship,” Delmont said, “cannot be reckoned by the clock. The moment I met Virginia I felt there was a real bond between us. We were together every minute almost after we met, and it seems to us now as though I’d always known and loved her.”[1]

Delmont faced a packed courtroom, including Arbuckle sitting between two policemen and wearing a new blue Norfolk jacket with a pair of knickerbocker trousers. His bloodshot eyes were fixed on Delmont while he squeezed and twisted his green golf cap in his fists and leaned forward in his chair just behind the railing that separated him from the defense counsel’s table. At times he yawned, either tired or bored, and said nothing to his lawyers.

After identifying herself and where she lived, Delmont drank deeply from a glass of cold water. She put the glass down, asked for warm water, and the inquest was held up while a coffee cupful was brought to her. As though by rote, with lines almost certainly rehearsed beforehand, Delmont repeated much of the same story she had told in her original statement, as it appeared in the press albeit with changes that were hardly negligible, which got the attention of everyone at the defense table.

With trembling hands, Delmont took sip after sip of warm water so as not to lose her voice or composure. She described everything in “minutest detail” from the trip to Selma to the Palace Hotel breakfast, where a bellhop handed Rappe a note inviting her to Arbuckle’s suite at the St. Francis Hotel. Delmont said the note read, “Come on up and say hello.” It bore Arbuckle’s signature.

Delmont made no mention of Fred Fishback or Ira Fortlouis playing any role in the invitation. Instead, she went on to the Labor Day party and once more reporters were forced to censor themselves rather and give only the gist. Instead of being forced into room 1219, Delmont no longer would say that Arbuckle had dragged Rappe by the wrist. Nor did she repeat that he had always wanted Rappe since 1916. Delmont made it seem as though Rappe entered that room of her own free will to use its bathroom. Then Arbuckle immediately followed Rappe. When she came out of the bathroom, Delmont saw them talk for a moment in the middle of the bedroom. “I can’t say if he went into the bathroom with her,” she said at one point. I guess he dragged her in.” But this last statement was not allowed to stand. Delmont, however, said she saw Arbuckle walk past Miss Rappe and close the connecting doors between 1220, the parlour room, and his bedroom. When a juror asked Delmont if she had verbally objected to when Arbuckle locked the door on himself and Rappe, Delmont said no.

Fifteen minutes passed before Delmont began to worry about Rappe. “I didn’t see why Virginia would not come out,” Delmont said. “I didn’t think it was nice for her to be in there with Mr. Arbuckle.”

Other accounts of the same testimony suggested that Delmont was alerted to something wrong not by Rappe’s silence but by her scream at one point. “What was the nature of the scream,” Leland asked. “As a woman in agony,” replied Delmont.

There was no response from inside room 1219 as Delmont tried to get Rappe’s attention. “Then I became angry,” Delmont said, “and I kicked ten or twelve times on the door of the room, but there wasn’t a sound.” After more time passed, Delmont called the desk. Harry Boyle took the call and came up at once and his presence in room 1220 prompted Arbuckle to open the door of 1219.

Arbuckle’s lawyers presented the coroner’s autopsy report that concluded that Rappe had chronic inflammation to her bladder but there were “no marks of violence on the body, no signs that the girl had been attacked in any way.” This disproved the allegation of an external cause or force (such as Arbuckle jumping on top of her) for the bladder rupture. But the pathologists also reported no evidence of pregnancy, previous abortions, or sexually transmitted diseases.1

Delmont continued, describing what happened after she, Zey Prevost, and Alice Blake entered Arbuckle’s bedroom up until Rappe was carried out. Throughout her testimony, however, Dr. Leland could hear that Delmont had changed her original story. Perhaps getting looks from Arbuckle’s lawyers, Dr. Leland interrupted Delmont and lectured her on the significance of her testimony as a complaining witness.

“I am here to tell just the truth,” she protested. Nevertheless, Leland warned the witness to “consider her statements well.” “Maybe I am leading you,” he continued, attempting to tease additional details from Delmont, whom he presumed to be fatigued from a night of Grand Jury testimony. “Sometimes people go to sleep and just say yes,” Leland said. “I’m not asleep,” Delmont replied and candidly added, “for I had a little hypodermic before I came here, and I am all right.”

Observers took her to mean an injection of morphine, of which dry mouth is a tell-tale side effect. Her drinking, too, raised eyebrows and made for the logical impression that she was an alcoholic—morphine being a temporary palliative for the side effects of alcohol abuse, including delirium tremens. Delmont admitted to drinking on the way up from Los Angeles to San Francisco—six whiskies while in Selma alone.

Dr. Leland asked about her prodigious capacity on Labor Day afternoon. Delmont admitted to drinking “eight or ten drinks of Scotch whisky.”

“Were you beginning to feel the effect of the drinks?” Leland asked. “Undoubtedly,” Delmont answered. She had been dancing, as well, and getting very hot in her black dress. “So I asked Mr. Sherman if he would mind if I slipped on some pajamas and he said, ‘No, certainly not’ and he took me into his room, got a suit of his pajamas from a dresser drawer and went out while I put them on.”

Dr. Leland asked Delmont about what Rappe and Arbuckle had to drink. Rappe may have had two or three drinks, both gin and orange juice. Rappe, said Delmont, was more interested in dancing and having a good time. Leland pressed on, asking if it were possible that Rappe had been drinking before Delmont had been allowed to join the Labor Day party.

“She was there only five minutes,” Delmont said in disbelief, “and common sense will tell you that she couldn’t have had many.”

_________________________________

© 2023 by www.fattyarbuckleofficial.com.

All rights reserved.